pytest fixture что это

Pytest fixture что это

Что пишут в блогах

2 декабря выступала в Костроме у Exactpro Systems с темой «Организация обучения джуниоров внутри команды». Уже готово видео! Ссылка на ютуб — https://youtu.be/UR9qZZ6IWBA

Привет! В блоге появляется мало новостей, потому что все переехало в telegram.

Стоимость в цвете — 2500 рублей самовывозом (доставка еще 500-600 рублей, информация по ней будет чуть позже)

Онлайн-тренинги

Что пишут в блогах (EN)

Software Testing

Разделы портала

Про инструменты

Оригинал статьи

Перевод: Ольга Алифанова

Продолжая рассказывать о чудесных возможностях Pytest, я хочу немного поговорить о старой, но прекрасной фиче – о фикстурах.

Фикстуры – интересная и часто смущающая новичков тема в Pytest. Вначале они кажутся контринтуитивными и попросту неправильными, но как только вы поймете, как это работает, фикстуры станут неотъемлемой частью хорошего кода Pytest.

Начнем с начала. Что такое фикстура? Это функция, несущая логику, применяемую в определенном контексте. Предположим для примера, что мы хотим протестировать библиотеку генератора случайных чисел по имени Rando. Мы можем использовать фикстуры для тестирования объект-экземпляра:

Эта фикстура возвращает экземпляр Rando по имени rando, который можно передавать в функции. Каждая функция получает свой собственный независимый экземпляр rando, который можно использовать в логическом теле функции. Это кажется довольно простым синтаксически, но тут происходит кое-что интересное.

Во-первых, мы не используем в коде объектно-ориентированное программирование. Две вышеуказанных функции не обязаны быть членами класса. Фикстура может использоваться этими функциями, и не должна сохранять состояние между тестами.

Приведу пример объектно-ориентированного псевдокода:

Это более традиционный подход, который тоже сработает с классами в Python. Удивительный красивый момент тут в том, что ООП не требуется для работы с Pytest. И, как оказывается, для работы с Pytest ООП лучше вовсе не использовать.

Чтобы понять, почему, давайте рассмотрим другой клевый аспект использования фикстур: фикстуры могут пользоваться другими фикстурами.

Предположим, что в вышеприведенном примере генератора случайных чисел можно создать и передать RandoSeed в экземпляр Rando. Если мы хотим одновременно проверить и использовать его, мы создадим такие фикстуры:

(Не волнуйтесь, если вам не знакома генерация случайных чисел. Суть тут в подходе к тесту, а не в конкретных тестируемых свойствах. Генерация случайных чисел – сложная штука).

В коде выше использование фикстуры для RandoSeed полностью отделено от экземпляра генератора случайных чисел. Оба можно использовать в тестах и фикстурах независимо. Нет нужны выделять эти тестовые функции в разные классы или пытаться настраивать или умалять функциональность. Все работает как и должно. Тесты можно добавлять, убирать и изменять индивидуально по необходимости, не жонглируя структурами классов.

Эти примеры – это только начало использования фикстур в Python, но они дают общее представление о том, как работают фикстуры и какие проблемы они решают. Жизнь с фикстурами Pytest хороша!

PyTest

Предисловие

По историческому призванию я SQL-щик. Однако судьба занесла меня на BigData и после этого понесла кривая — я освоил и Java, и Python, и функциональное программирование (изучение Scala стоит в списке). Собственно на одном из кусков проекта встала необходимость тестирования кода на Python. Ребята из QA посоветовали для этих целей PyTest, но даже они затруднились толком ответить чем этот зверь хорош. К сожалению, в русскоязычном сегменте информации по данному вопросу не так уж и много: как это используют в Yandex да и все по-хорошему. При этом описанное в этой статье выглядит достаточно сложно для человека начинающего путешествие по этой стезе. Не говоря уже об официальной документации — она приобрела для меня смысл лишь после того, как я разобрался с самим модулем по другим источникам. Не спорю, там написаны интересные вещи, но, к сожалению, совсем не для старта.

Юнит-тестирование Python

Что это и для чего рассказывать смысла не вижу — Википедия все равно знает больше. По поводу существующих модулей для Python хорошо описано на Хабре.

Вводная по необходимым знаниям

На описываемый момент знания Python у меня были достаточно поверхностны — я писал кое-какие несложные модули и знал стандартные вещи. Но при столкновении с PyTest мне пришлось пополнять багаж знаний декораторами тут и тут и конструкцией yield.

Преимущества и недостатки PyTest

1) Независимость от API (no boilerplate). Как код выглядит в том же unittest:

То же самое в PyTest:

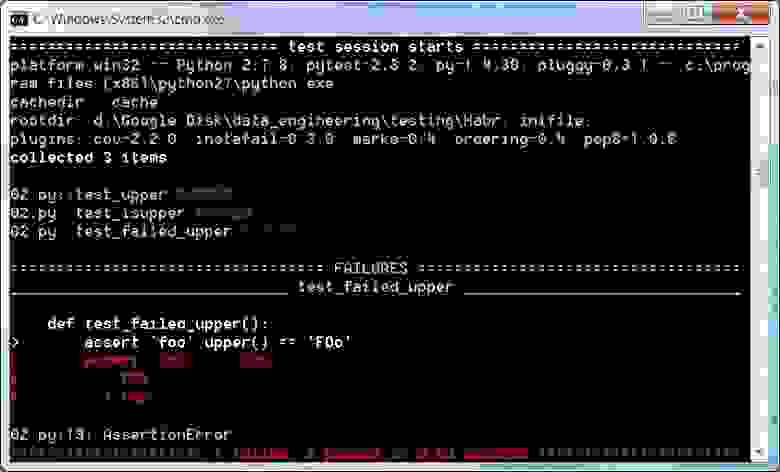

2) Подробный отчет. В том числе выгрузка в JUnitXML (для интеграции с Jenkins). Сам вид отчета может изменяться (включая цвета) дополнительными модулями (о них будет позднее отдельно). Ну и вообще цветной отчет в консоли выглядит удобнее — красные FAILED видны сразу.

3) Удобный assert (стандартный из Python). Не приходится держать в голове всю кучу различных assert’ов.

4) Динамические фикстуры всех уровней, которые могут вызываться как автоматически, так и для конкретных тестов.

5) Дополнительные возможности фикстур (возвращаемое значение, финализаторы, область видимости, объект request, автоиспользование, вложенные фикстуры)

6) Параметризация тестов, то есть запуск одного и того же теста с разными наборами параметров. Вообще это относится к пункту 5 «Дополнительные возможности фикстур», но возможность настолько хороша, что достойна отдельного пункта.

7) Метки (marks), позволяющие пропустить любой тест, пометить тест, как падающий (и это его ожидаемое поведение, что полезно при разработке) или просто именовать набор тестов, чтобы можно было запускать только его по имени.

8) Плагины. Данный модуль имеет достаточно большой список дополнительных модулей, которые можно установить отдельно.

9) Возможность запуска тестов написанных на unittest и nose, то есть полная обратная совместимость с ними.

Про недостатки, пусть их и не много, могу сказать следующее:

1) Отсутствие дополнительного уровня вложенности: Для модулей, классов, методов, функций в тестах есть соответствующий уровень. Но логика требует наличие дополнительного уровня testcase, когда та же одна функция может иметь несколько testcase’ов (например, проверка возращаемых значений и ошибок). Это частично компенсируется дополнительным модулем (плагином) pytest-describe, но там встает проблема отсутствия соответствующего уровня фикстуры (scope = “describe”). С этим конечно можно жить, но в некоторых ситуациях может нарушать главный принцип PyTest — «все для простоты и удобства».

2) Необходимость отдельной установки модуля, в том числе в продакшене. Все-таки unittest и doctest входят в базовый инструментарий Python и не требуют дополнительных телодвижений.

3) Для использования PyTest требуется немного больше знаний Python, чем для того же unittest (см. «Вводная по необходимым знаниям»).

Подробное описание модуля и его возможностей под катом.

Запуск тестов

Базовые фикстуры

В данном случае фикстурами я называю функции и методы, которые запускаются для создания соответствующего окружения для теста. PyTest, как и unittest, имеет названия для фикстур всех уровней:

Данный пример достаточно полно показывает иерархию и повторяемость каждого уровня фикстур (например, setup_function вызывается перед каждым вызовом функции, а setup_module – только один раз для всего модуля). Также можно видеть, что уровень фикстуры по умолчанию — функция/метод (фикстура setup и teardown).

Расширенные фикстуры

Вопрос что делать, если для части тестов нужно определенное окружение, а для других нет? Разносить по разным модулям или классам? Не выглядит очень удобно и красиво. На помощь приходят расширенные фикстуры PyTest.

Итак, для создания расширенной фикстуры в PyTest необходимо:

1) импортировать модуль pytest

2) использовать декоратор @pytest.fixture(), чтобы обозначить что данная функция является фикстурой

3) задать уровень фикстуры (scope). Возможные значения “function”, “cls”, “module”, “session”. Значение по умолчанию = “function”.

4) если необходим вызов teardown для этой фикстуры, то надо добавить в него финализатор (через метод addfinalizer объекта request передаваемого в фикстуру или же через использование конструкции yield)

5) добавить имя данной фикстуры в список параметров функции

Вызов расширенных фикстур

Следует добавить, что расширенные фикстуры можно вызывать еще двумя способами:

1) декорирование теста декоратором @pytest.mark.usefixtures()

2) использование флага autouse для фикстуры. Однако следует использовать данную возможность с осторожностью, так как в итоге вы можете получить неожиданное поведение тестов.

3) собственно описанный выше способ через параметры теста

Вот так будет выглядеть предыдущий пример:

teardown расширенной фикстуры

Как было сказано выше, если необходим вызов teardown для определенной расширенной фикстуры, то можно реализовать его двумя способами:

1) добавив в фикстуру финализатор (через метод addfinalizer объекта request передаваемого в фикстуру

2) через использование конструкции yield (начиная с PyTest версии 2.4)

Первый способ мы рассмотрели в примере создания расширенной фикстуры. Теперь же просто продемонстрируем ту же самую функциональность через использование yield. Следует заметить, что для использования yield при декорировании функции, как фикстуры, необходимо использовать декоратор @pytest.yield_fixture(), а не @pytest.fixture():

Вывод не буду добавлять в текст в связи с тем, что он совпадает с вариантом с финализатором.

Возвращаемое фикстурой значение

Как возможность, фикстура в PyTest может возвращать что-нибудь в тест через return. Будь то какое-то значение состояние, так и объект (например, файл).

Уровень фикстуры (scope)

Уровень фикстуры может принимать следующие возможные значения “function”, “cls”, “module”, “session”. Значение по умолчанию = “function”.\

function – фикстура запускается для каждого теста

cls – фикстура запускается для каждого класса

module – фикстура запускается для каждого модуля

session – фикстура запускается для каждой сессии (то есть фактически один раз)

Например, в предыдущем примере можно поменять scope на function и вызывать подключение к базе данных и отключение для каждого теста:

Также фикстуры можно описывать в файле conftest.py, который автоматически импортируется PyTest. При этом фикстура может иметь любой уровень (только через описание в этом файле можно создать фикстуру с уровнем «сессия»).

Например, создадим отдельную папку session scope с файлом conftest.py и двумя файлами тестов (напомню, что чтобы PyTest автоматически импортировал модули их названия должны начинаться с test_. Хотя это поведение можно изменить.):

Объект request

В примере создания расширенной фикстуры мы передали в нее параметр request. Это было сделано чтобы через его метод addfinalizer добавить финализатор. Однако этот объект имеет также достаточно много атрибутов и других методов (полный список в официальном API).

Параметризация

Параметризация — это способ запустить один и тот же тест с разным набором входных параметров. Например, у нас есть функция, которая добавляет знак вопроса к строке, если она длиннее 5 символов, восклицательный знак — менее 5 символов и точку, если в строке ровно 5 символов. Соответственно вместо того, чтобы писать три теста, мы можем написать один, но вызываемый с разными параметрами.

Задать параметры для теста можно двумя способами:

1) Через значение параметра params фикстуры, в который нужно передать массив значений.

То есть фактически фикстура в данном случае представляет собой обертку, передающую параметры. А в сам тест они передаются через атрибут param объекта request, описанного выше.

2) Через декоратор (метку) @pytest.mark.parametrize, в который передается список названий переменных и массив их значений.

Итак первый способ.

Все отлично работает кроме одной неприятной детали — по названию теста невозможно понять, что за параметр был передан в тест. И в этом случае выручает параметр ids фикстуры. Он принимает или список имен тестов (его длина должна совпадать с количеством оных), или функцию, которая сгенерирует итоговое название.

В данном случае я запустил PyTest с дополнительным параметром —collect-only, который позволяет собрать все тесты, порожденные параметризацией, без их запуска.

Второй способ имеет одно преимущество: если указать несколько меток с разными параметрами, то в итоге тест будет запущен со всеми возможными наборами параметров (то есть декартово произведение параметров).

В метке параметризации также можно передать параметр ids, ответственный за отображение параметров в выводе аналогично первому способу задания параметров:

Вызов нескольких фикстур и фикстуры, использующие фикстуры

PyTest не ограничивает список фикстур вызываемый для теста.

Также любая фикстура может также вызывать к исполнению любое количество фикстур до себя:

Метки

PyTest поддерживает класс декораторов @pytest.mark называемый «метками» (marks). Базовый список включает в себя следующие метки:

1) @pytest.mark.parametrize — для параметризации тестов (было рассмотрено выше)

2) @pytest.mark.xfail – помечает, что тест должен не проходить и PyTest будет воспринимать это, как ожидаемое поведение (полезно, как временная метка для тестов на разрабатываемые функции). Также эта метка может принимать условие, при котором тест будет помечаться данной меткой.

3) @pytest.mark.skipif – позволяет задать условие при выполнении которогл тест будет пропущен

4) @pytest.mark.usefixtures – позволяет перечислить все фикстуры, вызываемые для теста

Также меткой можно пометить не только тест, но и класс, модуль (задается через изменение атрибута импортируемого модуля) или его запуск, получаемый через параметризацию (см. следующий пример).

Обработка исключений

Конечно же, как полноценный модуль для тестирования, PyTest также позволяет проверять корректность возвращаемых исключений при помощи «with pytest.raises()».

Запуск тестов по имени или ID

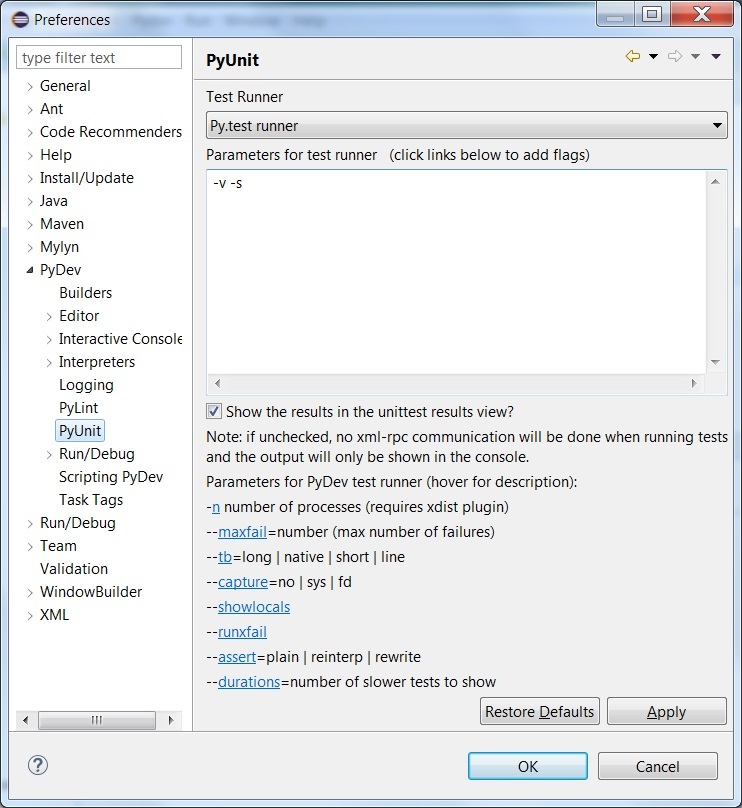

Интеграция с PyDev в Eclipse

Хотелось бы упомянуть, что PyTest интегрирован в компонент PyUnit модуля PyDev для Eclipse. Просто в настройках надо указать, что надо использовать именно его.

Дополнительные модули

PyTest имеет массу дополнительных модулей.

Могу лишь упомянуть те модули, которые меня заинтересовали и почему (детали о модулях можно прочитать по ссылке выше):

pytest-describe – добавляет еще один уровень абстракции (модуль-описание-функция, как эквивалент модуль-функция-testcase).

pytest-instafail – изменяет базовое поведение модуля таким образом что все ошибки и падения показываются в процессе исполнения, а не окончанию работы всей сесссии.

pytest-marks – позволяет задавать несколько меток одновременно для теста:

pytest-ordering — позволяет задавать вручную порядок запуска тестов через метку Run.

pytest-pep8 – позволяет проверять код тестов на соответствие соглашения pep-8.

pytest-smartcov — позволяет проверять покрытие кода тестам, как полное, так и частичное.

pytest-timeout — позволяет завершать тесты по таймауту, через параметр командной строки или специальной метки.

pytest-sugar — позволяет изменить внешний вид вывода PyTest’а, добавляя прогресс бар и процент выполнения. Выглядит красиво, пускай местами и не очень информативно.

pytest fixtures: explicit, modular, scalable¶

Software test fixtures initialize test functions. They provide a fixed baseline so that tests execute reliably and produce consistent, repeatable, results. Initialization may setup services, state, or other operating environments. These are accessed by test functions through arguments; for each fixture used by a test function there is typically a parameter (named after the fixture) in the test function’s definition.

pytest fixtures offer dramatic improvements over the classic xUnit style of setup/teardown functions:

fixtures have explicit names and are activated by declaring their use from test functions, modules, classes or whole projects.

fixtures are implemented in a modular manner, as each fixture name triggers a fixture function which can itself use other fixtures.

fixture management scales from simple unit to complex functional testing, allowing to parametrize fixtures and tests according to configuration and component options, or to re-use fixtures across function, class, module or whole test session scopes.

teardown logic can be easily, and safely managed, no matter how many fixtures are used, without the need to carefully handle errors by hand or micromanage the order that cleanup steps are added.

Control logging and access log entries.

Store and retrieve values across pytest runs.

Provide a dict injected into the docstests namespace.

Access to configuration values, pluginmanager and plugin hooks.

Add extra properties to the test.

Add extra properties to the test suite.

Record warnings emitted by test functions.

Provide information on the executing test function.

Provide a temporary test directory to aid in running, and testing, pytest plugins.

Provide a pathlib.Path object to a temporary directory which is unique to each test function.

Make session-scoped temporary directories and return pathlib.Path objects.

What fixtures are¶

Before we dive into what fixtures are, let’s first look at what a test is.

In the simplest terms, a test is meant to look at the result of a particular behavior, and make sure that result aligns with what you would expect. Behavior is not something that can be empirically measured, which is why writing tests can be challenging.

“Behavior” is the way in which some system acts in response to a particular situation and/or stimuli. But exactly how or why something is done is not quite as important as what was done.

You can think of a test as being broken down into four steps:

Arrange

Assert

Cleanup

Arrange is where we prepare everything for our test. This means pretty much everything except for the “act”. It’s lining up the dominoes so that the act can do its thing in one, state-changing step. This can mean preparing objects, starting/killing services, entering records into a database, or even things like defining a URL to query, generating some credentials for a user that doesn’t exist yet, or just waiting for some process to finish.

Act is the singular, state-changing action that kicks off the behavior we want to test. This behavior is what carries out the changing of the state of the system under test (SUT), and it’s the resulting changed state that we can look at to make a judgement about the behavior. This typically takes the form of a function/method call.

Cleanup is where the test picks up after itself, so other tests aren’t being accidentally influenced by it.

At it’s core, the test is ultimately the act and assert steps, with the arrange step only providing the context. Behavior exists between act and assert.

Back to fixtures¶

“Fixtures”, in the literal sense, are each of the arrange steps and data. They’re everything that test needs to do its thing.

At a basic level, test functions request fixtures by declaring them as arguments, as in the test_ehlo(smtp_connection): in the previous example.

In pytest, “fixtures” are functions you define that serve this purpose. But they don’t have to be limited to just the arrange steps. They can provide the act step, as well, and this can be a powerful technique for designing more complex tests, especially given how pytest’s fixture system works. But we’ll get into that further down.

Tests don’t have to be limited to a single fixture, either. They can depend on as many fixtures as you want, and fixtures can use other fixtures, as well. This is where pytest’s fixture system really shines.

Don’t be afraid to break things up if it makes things cleaner.

“Requesting” fixtures¶

So fixtures are how we prepare for a test, but how do we tell pytest what tests and fixtures need which fixtures?

At a basic level, test functions request fixtures by declaring them as arguments, as in the test_my_fruit_in_basket(my_fruit, fruit_basket): in the previous example.

At a basic level, pytest depends on a test to tell it what fixtures it needs, so we have to build that information into the test itself. We have to make the test “request” the fixtures it depends on, and to do this, we have to list those fixtures as parameters in the test function’s “signature” (which is the def test_something(blah, stuff, more): line).

When pytest goes to run a test, it looks at the parameters in that test function’s signature, and then searches for fixtures that have the same names as those parameters. Once pytest finds them, it runs those fixtures, captures what they returned (if anything), and passes those objects into the test function as arguments.

Quick example¶

In this example, test_fruit_salad “requests” fruit_bowl (i.e. def test_fruit_salad(fruit_bowl): ), and when pytest sees this, it will execute the fruit_bowl fixture function and pass the object it returns into test_fruit_salad as the fruit_bowl argument.

Here’s roughly what’s happening if we were to do it by hand:

Fixtures can request other fixtures¶

One of pytest’s greatest strengths is its extremely flexible fixture system. It allows us to boil down complex requirements for tests into more simple and organized functions, where we only need to have each one describe the things they are dependent on. We’ll get more into this further down, but for now, here’s a quick example to demonstrate how fixtures can use other fixtures:

Notice that this is the same example from above, but very little changed. The fixtures in pytest request fixtures just like tests. All the same requesting rules apply to fixtures that do for tests. Here’s how this example would work if we did it by hand:

Fixtures are reusable¶

One of the things that makes pytest’s fixture system so powerful, is that it gives us the abilty to define a generic setup step that can reused over and over, just like a normal function would be used. Two different tests can request the same fixture and have pytest give each test their own result from that fixture.

This is extremely useful for making sure tests aren’t affected by each other. We can use this system to make sure each test gets its own fresh batch of data and is starting from a clean state so it can provide consistent, repeatable results.

Here’s an example of how this can come in handy:

Each test here is being given its own copy of that list object, which means the order fixture is getting executed twice (the same is true for the first_entry fixture). If we were to do this by hand as well, it would look something like this:

A test/fixture can request more than one fixture at a time¶

Tests and fixtures aren’t limited to requesting a single fixture at a time. They can request as many as they like. Here’s another quick example to demonstrate:

Fixtures can be requested more than once per test (return values are cached)¶

Fixtures can also be requested more than once during the same test, and pytest won’t execute them again for that test. This means we can request fixtures in multiple fixtures that are dependent on them (and even again in the test itself) without those fixtures being executed more than once.

If a requested fixture was executed once for every time it was requested during a test, then this test would fail because both append_first and test_string_only would see order as an empty list (i.e. [] ), but since the return value of order was cached (along with any side effects executing it may have had) after the first time it was called, both the test and append_first were referencing the same object, and the test saw the effect append_first had on that object.

Autouse fixtures (fixtures you don’t have to request)¶

Sometimes you may want to have a fixture (or even several) that you know all your tests will depend on. “Autouse” fixtures are a convenient way to make all tests automatically request them. This can cut out a lot of redundant requests, and can even provide more advanced fixture usage (more on that further down).

We can make a fixture an autouse fixture by passing in autouse=True to the fixture’s decorator. Here’s a simple example for how they can be used:

In this example, the append_first fixture is an autouse fixture. Because it happens automatically, both tests are affected by it, even though neither test requested it. That doesn’t mean they can’t be requested though; just that it isn’t necessary.

Scope: sharing fixtures across classes, modules, packages or session¶

The next example puts the fixture function into a separate conftest.py file so that tests from multiple test modules in the directory can access the fixture function:

Here, the test_ehlo needs the smtp_connection fixture value. pytest will discover and call the @pytest.fixture marked smtp_connection fixture function. Running the test looks like this:

You see the two assert 0 failing and more importantly you can also see that the exactly same smtp_connection object was passed into the two test functions because pytest shows the incoming argument values in the traceback. As a result, the two test functions using smtp_connection run as quick as a single one because they reuse the same instance.

If you decide that you rather want to have a session-scoped smtp_connection instance, you can simply declare it:

Fixture scopes¶

Fixtures are created when first requested by a test, and are destroyed based on their scope :

function : the default scope, the fixture is destroyed at the end of the test.

class : the fixture is destroyed during teardown of the last test in the class.

module : the fixture is destroyed during teardown of the last test in the module.

package : the fixture is destroyed during teardown of the last test in the package.

session : the fixture is destroyed at the end of the test session.

Pytest only caches one instance of a fixture at a time, which means that when using a parametrized fixture, pytest may invoke a fixture more than once in the given scope.

Dynamic scope¶

This can be especially useful when dealing with fixtures that need time for setup, like spawning a docker container. You can use the command-line argument to control the scope of the spawned containers for different environments. See the example below.

Fixture errors¶

pytest does its best to put all the fixtures for a given test in a linear order so that it can see which fixture happens first, second, third, and so on. If an earlier fixture has a problem, though, and raises an exception, pytest will stop executing fixtures for that test and mark the test as having an error.

When a test is marked as having an error, it doesn’t mean the test failed, though. It just means the test couldn’t even be attempted because one of the things it depends on had a problem.

This is one reason why it’s a good idea to cut out as many unnecessary dependencies as possible for a given test. That way a problem in something unrelated isn’t causing us to have an incomplete picture of what may or may not have issues.

Here’s a quick example to help explain:

Teardown/Cleanup (AKA Fixture finalization)¶

When we run our tests, we’ll want to make sure they clean up after themselves so they don’t mess with any other tests (and also so that we don’t leave behind a mountain of test data to bloat the system). Fixtures in pytest offer a very useful teardown system, which allows us to define the specific steps necessary for each fixture to clean up after itself.

This system can be leveraged in two ways.

1. yield fixtures (recommended)¶

Once pytest figures out a linear order for the fixtures, it will run each one up until it returns or yields, and then move on to the next fixture in the list to do the same thing.

Once the test is finished, pytest will go back down the list of fixtures, but in the reverse order, taking each one that yielded, and running the code inside it that was after the yield statement.

As a simple example, let’s say we want to test sending email from one user to another. We’ll have to first make each user, then send the email from one user to the other, and finally assert that the other user received that message in their inbox. If we want to clean up after the test runs, we’ll likely have to make sure the other user’s mailbox is emptied before deleting that user, otherwise the system may complain.

Here’s what that might look like:

Because receiving_user is the last fixture to run during setup, it’s the first to run during teardown.

Handling errors for yield fixture¶

If a yield fixture raises an exception before yielding, pytest won’t try to run the teardown code after that yield fixture’s yield statement. But, for every fixture that has already run successfully for that test, pytest will still attempt to tear them down as it normally would.

2. Adding finalizers directly¶

While yield fixtures are considered to be the cleaner and more straighforward option, there is another choice, and that is to add “finalizer” functions directly to the test’s request-context object. It brings a similar result as yield fixtures, but requires a bit more verbosity.

In order to use this approach, we have to request the request-context object (just like we would request another fixture) in the fixture we need to add teardown code for, and then pass a callable, containing that teardown code, to its addfinalizer method.

We have to be careful though, because pytest will run that finalizer once it’s been added, even if that fixture raises an exception after adding the finalizer. So to make sure we don’t run the finalizer code when we wouldn’t need to, we would only add the finalizer once the fixture would have done something that we’d need to teardown.

Here’s how the previous example would look using the addfinalizer method:

It’s a bit longer than yield fixtures and a bit more complex, but it does offer some nuances for when you’re in a pinch.

Safe teardowns¶

The fixture system of pytest is very powerful, but it’s still being run by a computer, so it isn’t able to figure out how to safely teardown everything we throw at it. If we aren’t careful, an error in the wrong spot might leave stuff from our tests behind, and that can cause further issues pretty quickly.

For example, consider the following tests (based off of the mail example from above):

This version is a lot more compact, but it’s also harder to read, doesn’t have a very descriptive fixture name, and none of the fixtures can be reused easily.

There’s also a more serious issue, which is that if any of those steps in the setup raise an exception, none of the teardown code will run.

One option might be to go with the addfinalizer method instead of yield fixtures, but that might get pretty complex and difficult to maintain (and it wouldn’t be compact anymore).

Safe fixture structure¶

The safest and simplest fixture structure requires limiting fixtures to only making one state-changing action each, and then bundling them together with their teardown code, as the email examples above showed.

The chance that a state-changing operation can fail but still modify state is neglibible, as most of these operations tend to be transaction-based (at least at the level of testing where state could be left behind). So if we make sure that any successful state-changing action gets torn down by moving it to a separate fixture function and separating it from other, potentially failing state-changing actions, then our tests will stand the best chance at leaving the test environment the way they found it.

For an example, let’s say we have a website with a login page, and we have access to an admin API where we can generate users. For our test, we want to:

Create a user through that admin API

Launch a browser using Selenium

Go to the login page of our site

Log in as the user we created

Assert that their name is in the header of the landing page

We wouldn’t want to leave that user in the system, nor would we want to leave that browser session running, so we’ll want to make sure the fixtures that create those things clean up after themselves.

Here’s what that might look like:

For this example, certain fixtures (i.e. base_url and admin_credentials ) are implied to exist elsewhere. So for now, let’s assume they exist, and we’re just not looking at them.

Fixture availability¶

Fixture availability is determined from the perspective of the test. A fixture is only available for tests to request if they are in the scope that fixture is defined in. If a fixture is defined inside a class, it can only be requested by tests inside that class. But if a fixture is defined inside the global scope of the module, than every test in that module, even if it’s defined inside a class, can request it.

Similarly, a test can also only be affected by an autouse fixture if that test is in the same scope that autouse fixture is defined in (see Autouse fixtures are executed first within their scope ).

A fixture can also request any other fixture, no matter where it’s defined, so long as the test requesting them can see all fixtures involved.

For example, here’s a test file with a fixture ( outer ) that requests a fixture ( inner ) from a scope it wasn’t defined in:

From the tests’ perspectives, they have no problem seeing each of the fixtures they’re dependent on:

conftest.py : sharing fixtures across multiple files¶

The conftest.py file serves as a means of providing fixtures for an entire directory. Fixtures defined in a conftest.py can be used by any test in that package without needing to import them (pytest will automatically discover them).

You can have multiple nested directories/packages containing your tests, and each directory can have its own conftest.py with its own fixtures, adding on to the ones provided by the conftest.py files in parent directories.

For example, given a test file structure like this:

The boundaries of the scopes can be visualized like this:

The directories become their own sort of scope where fixtures that are defined in a conftest.py file in that directory become available for that whole scope.

The first fixture the test finds is the one that will be used, so fixtures can be overriden if you need to change or extend what one does for a particular scope.

Fixtures from third-party plugins¶

Fixtures don’t have to be defined in this structure to be available for tests, though. They can also be provided by third-party plugins that are installed, and this is how many pytest plugins operate. As long as those plugins are installed, the fixtures they provide can be requested from anywhere in your test suite.

Because they’re provided from outside the structure of your test suite, third-party plugins don’t really provide a scope like conftest.py files and the directories in your test suite do. As a result, pytest will search for fixtures stepping out through scopes as explained previously, only reaching fixtures defined in plugins last.

For example, given the following file structure:

Sharing test data¶

If you want to make test data from files available to your tests, a good way to do this is by loading these data in a fixture for use by your tests. This makes use of the automatic caching mechanisms of pytest.

Another good approach is by adding the data files in the tests folder. There are also community plugins available to help managing this aspect of testing, e.g. pytest-datadir and pytest-datafiles.

Fixture instantiation order¶

When pytest wants to execute a test, once it knows what fixtures will be executed, it has to figure out the order they’ll be executed in. To do this, it considers 3 factors:

Names of fixtures or tests, where they’re defined, the order they’re defined in, and the order fixtures are requested in have no bearing on execution order beyond coincidence. While pytest will try to make sure coincidences like these stay consistent from run to run, it’s not something that should be depended on. If you want to control the order, it’s safest to rely on these 3 things and make sure dependencies are clearly established.

Higher-scoped fixtures are executed first¶

Within a function request for fixtures, those of higher-scopes (such as session ) are executed before lower-scoped fixtures (such as function or class ).

The test will pass because the larger scoped fixtures are executing first.

The order breaks down to this:

Fixtures of the same order execute based on dependencies¶

If we map out what depends on what, we get something that look like this:

The rules provided by each fixture (as to what fixture(s) each one has to come after) are comprehensive enough that it can be flattened to this:

Enough information has to be provided through these requests in order for pytest to be able to figure out a clear, linear chain of dependencies, and as a result, an order of operations for a given test. If there’s any ambiguity, and the order of operations can be interpreted more than one way, you should assume pytest could go with any one of those interpretations at any point.

This isn’t necessarily bad, but it’s something to keep in mind. If the order they execute in could affect the behavior a test is targetting, or could otherwise influence the result of a test, then the order should be defined explicitely in a way that allows pytest to linearize/”flatten” that order.

Autouse fixtures are executed first within their scope¶

Autouse fixtures are assumed to apply to every test that could reference them, so they are executed before other fixtures in that scope. Fixtures that are requested by autouse fixtures effectively become autouse fixtures themselves for the tests that the real autouse fixture applies to.

So if the test file looked like this:

the graph would look like this:

Because c can now be put above d in the graph, pytest can once again linearize the graph to this:

In this example, c makes b and a effectively autouse fixtures as well.

Be careful with autouse, though, as an autouse fixture will automatically execute for every test that can reach it, even if they don’t request it. For example, consider this file:

But just because one autouse fixture requested a non-autouse fixture, that doesn’t mean the non-autouse fixture becomes an autouse fixture for all contexts that it can apply to. It only effectively becomes an auotuse fixture for the contexts the real autouse fixture (the one that requested the non-autouse fixture) can apply to.

For example, take a look at this test file:

It would break down to something like this:

Running multiple assert statements safely¶

Sometimes you may want to run multiple asserts after doing all that setup, which makes sense as, in more complex systems, a single action can kick off multiple behaviors. pytest has a convenient way of handling this and it combines a bunch of what we’ve gone over so far.

All that’s needed is stepping up to a larger scope, then having the act step defined as an autouse fixture, and finally, making sure all the fixtures are targetting that highler level scope.

Let’s take a look at how we can structure that so we can run multiple asserts without having to repeat all those steps again.

For this example, certain fixtures (i.e. base_url and admin_credentials ) are implied to exist elsewhere. So for now, let’s assume they exist, and we’re just not looking at them.

Notice that the methods are only referencing self in the signature as a formality. No state is tied to the actual test class as it might be in the unittest.TestCase framework. Everything is managed by the pytest fixture system.

Each method only has to request the fixtures that it actually needs without worrying about order. This is because the act fixture is an autouse fixture, and it made sure all the other fixtures executed before it. There’s no more changes of state that need to take place, so the tests are free to make as many non-state-changing queries as they want without risking stepping on the toes of the other tests.

The login fixture is defined inside the class as well, because not every one of the other tests in the module will be expecting a successful login, and the act may need to be handled a little differently for another test class. For example, if we wanted to write another test scenario around submitting bad credentials, we could handle it by adding something like this to the test file:

Fixtures can introspect the requesting test context¶

Fixture functions can accept the request object to introspect the “requesting” test function, class or module context. Further extending the previous smtp_connection fixture example, let’s read an optional server URL from the test module which uses our fixture:

We use the request.module attribute to optionally obtain an smtpserver attribute from the test module. If we just execute again, nothing much has changed:

Let’s quickly create another test module that actually sets the server URL in its module namespace:

voila! The smtp_connection fixture function picked up our mail server name from the module namespace.

Using markers to pass data to fixtures¶

Using the request object, a fixture can also access markers which are applied to a test function. This can be useful to pass data into a fixture from a test:

Factories as fixtures¶

The “factory as fixture” pattern can help in situations where the result of a fixture is needed multiple times in a single test. Instead of returning data directly, the fixture instead returns a function which generates the data. This function can then be called multiple times in the test.

Factories can have parameters as needed:

If the data created by the factory requires managing, the fixture can take care of that:

Parametrizing fixtures¶

Fixture functions can be parametrized in which case they will be called multiple times, each time executing the set of dependent tests, i. e. the tests that depend on this fixture. Test functions usually do not need to be aware of their re-running. Fixture parametrization helps to write exhaustive functional tests for components which themselves can be configured in multiple ways.

Extending the previous example, we can flag the fixture to create two smtp_connection fixture instances which will cause all tests using the fixture to run twice. The fixture function gets access to each parameter through the special request object:

We see that our two test functions each ran twice, against the different smtp_connection instances. Note also, that with the mail.python.org connection the second test fails in test_ehlo because a different server string is expected than what arrived.

Numbers, strings, booleans and None will have their usual string representation used in the test ID. For other objects, pytest will make a string based on the argument name. It is possible to customise the string used in a test ID for a certain fixture value by using the ids keyword argument:

The above shows how ids can be either a list of strings to use or a function which will be called with the fixture value and then has to return a string to use. In the latter case if the function returns None then pytest’s auto-generated ID will be used.

Running the above tests results in the following test IDs being used:

Using marks with parametrized fixtures¶

Running this test will skip the invocation of data_set with value 2 :

Modularity: using fixtures from a fixture function¶

In addition to using fixtures in test functions, fixture functions can use other fixtures themselves. This contributes to a modular design of your fixtures and allows re-use of framework-specific fixtures across many projects. As a simple example, we can extend the previous example and instantiate an object app where we stick the already defined smtp_connection resource into it:

Here we declare an app fixture which receives the previously defined smtp_connection fixture and instantiates an App object with it. Let’s run it:

Note that the app fixture has a scope of module and uses a module-scoped smtp_connection fixture. The example would still work if smtp_connection was cached on a session scope: it is fine for fixtures to use “broader” scoped fixtures but not the other way round: A session-scoped fixture could not use a module-scoped one in a meaningful way.

Automatic grouping of tests by fixture instances¶

pytest minimizes the number of active fixtures during test runs. If you have a parametrized fixture, then all the tests using it will first execute with one instance and then finalizers are called before the next fixture instance is created. Among other things, this eases testing of applications which create and use global state.

The following example uses two parametrized fixtures, one of which is scoped on a per-module basis, and all the functions perform print calls to show the setup/teardown flow:

Let’s run the tests in verbose mode and with looking at the print-output:

You can see that the parametrized module-scoped modarg resource caused an ordering of test execution that lead to the fewest possible “active” resources. The finalizer for the mod1 parametrized resource was executed before the mod2 resource was setup.

The otherarg parametrized resource (having function scope) was set up before and teared down after every test that used it.

Use fixtures in classes and modules with usefixtures ¶

Sometimes test functions do not directly need access to a fixture object. For example, tests may require to operate with an empty directory as the current working directory but otherwise do not care for the concrete directory. Here is how you can use the standard tempfile and pytest fixtures to achieve it. We separate the creation of the fixture into a conftest.py file:

and declare its use in a test module via a usefixtures marker:

Due to the usefixtures marker, the cleandir fixture will be required for the execution of each test method, just as if you specified a “cleandir” function argument to each of them. Let’s run it to verify our fixture is activated and the tests pass:

You can specify multiple fixtures like this:

and you may specify fixture usage at the test module level using pytestmark :

It is also possible to put fixtures required by all tests in your project into an ini-file:

Note this mark has no effect in fixture functions. For example, this will not work as expected:

Currently this will not generate any error or warning, but this is intended to be handled by #3664.

Overriding fixtures on various levels¶

In relatively large test suite, you most likely need to override a global or root fixture with a locally defined one, keeping the test code readable and maintainable.

Override a fixture on a folder (conftest) level¶

Given the tests file structure is:

Override a fixture on a test module level¶

Given the tests file structure is:

In the example above, a fixture with the same name can be overridden for certain test module.

Override a fixture with direct test parametrization¶

Given the tests file structure is:

In the example above, a fixture value is overridden by the test parameter value. Note that the value of the fixture can be overridden this way even if the test doesn’t use it directly (doesn’t mention it in the function prototype).

Override a parametrized fixture with non-parametrized one and vice versa¶

Given the tests file structure is:

In the example above, a parametrized fixture is overridden with a non-parametrized version, and a non-parametrized fixture is overridden with a parametrized version for certain test module. The same applies for the test folder level obviously.

Using fixtures from other projects¶

In case you want to use fixtures from a project that does not use entry points, you can define pytest_plugins in your top conftest.py file to register that module as a plugin.

Suppose you have some fixtures in mylibrary.fixtures and you want to reuse them into your app/tests directory.

All you need to do is to define pytest_plugins in app/tests/conftest.py pointing to that module.

Sometimes users will import fixtures from other projects for use, however this is not recommended: importing fixtures into a module will register them in pytest as defined in that module.